How long do peacock butterflies live?

True, in Friedrichsruhe you can also see butterflies typical of the middle zone. — The peacock eye is a unique European butterfly that lives for about 10 months and overwinters in basements or hollows of trees.

Interesting materials:

What is needed to register an individual entrepreneur? What do you need to open your own car wash? What do you need to transport a cat abroad? What do you need to build a gaming computer? What does it take to be a successful public speaker? What do you need for category D? What should you write at the end of your presentation? What should you prepare for the New Year? What needs to be done to make dill sprout faster? What needs to be done to get geraniums to take root?

How many limbs does a caterpillar have?

Most species of caterpillars have only three pairs of true legs, also called pectoral legs. All other limbs that can be seen on the larva are false. True and false caterpillar legs have certain differences, but are similar in structure. Like any other insect, their limbs consist of the following parts:

- basin;

1-thoracic, 2-abdominal legs.

- trochanter;

- hip;

- shin;

- paw.

Thoracic legs of a caterpillar

The real legs of the caterpillar are called pectoral legs because of their location. Each thoracic segment of the larval body has one pair of true limbs. They are poorly developed and play a smaller role in movement compared to the abdominal ones.

There are claws at the ends of the thoracic limbs. The length and shape of these claws can vary significantly depending on the type of caterpillar.

Abdominal legs of a caterpillar

Caterpillars have legs.

Most species have 5 pairs of false limbs. They are located on segments 3, 4, 5, 6 and 10 of the caterpillar's body. There are special hooks on the abdominal legs. They help the larva to hold firmly on various vertical and horizontal surfaces, and can be arranged in a circle or in rows.

At the edge of the abdominal leg there is a movable sole with claws. It can retract inward or bulge outward. The sole of the larva can be of two types:

- rounded. The hooks on such a sole are located in a circle, and the muscle that activates it is located in the center;

- reduced. The outer part of the sole of this type is almost undeveloped. The hooks are attached to its inner edges, and the muscles to the outer edges. The outer edge of the sole may also be significantly sclerotized.

Different caterpillar legs.

Features of individual types

Some caterpillars have special respiratory structures that allow them to survive in aquatic habitats. For example, the larvae of some pyramidal clams (family Pyralidae) are aquatic, and several members of the genus Hyposmocoma (family Cosmopterigidae) have an amphibious caterpillar stage. Some caterpillars spin silken sheaths that provide protective coverings. They often have leaves, pebbles and more woven into them, making them look like part of their natural surroundings.

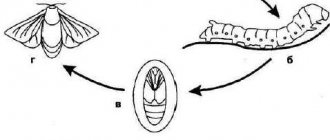

Life cycle

In their development, all representatives of the order Lepidoptera go through 4 stages: egg, caterpillar, pupa, butterfly. After mating, female insects lay eggs, which can develop from several days to months. The duration of the period depends on temperature conditions. The caterpillar easily gnaws through the shell of the egg. Under unfavorable weather conditions, the larva overwinters in the egg and only when spring comes does it emerge. Hungry caterpillars often eat the remains of their “shelter.”

Caterpillars

How long do caterpillars live is a question that can be found quite often on the Internet. The duration of this phase of insect development depends on the species and can last several days or years. This is due to the fact that northern butterflies hibernate without completing their development cycle.

Interesting!

The moth, which lives in harsh northern regions, can remain in the caterpillar stage for about 14 years.

The caterpillar has several phases of development. They are characterized not only by changes in the color and size of the insect, but also by certain structural features. During its life, an insect undergoes a certain number of moults, which depend on its membership in a particular biological species. Typically, the larva molts 4 times; for representatives of certain species, this number can vary from 5 to 7. Under unfavorable external conditions, the growth period of the insect is prolonged, and the number of molts increases.

On a note!

The clothes caterpillar can molt 4 or 40 times.

Before this process begins, they stop feeding, become motionless and hide in secluded places. Their skin stretches and their head seems to shrink in size. Having shed the old shell, the caterpillar can eat it. Having gone through all stages of molting, insects move on to a new life stage.

Pupation of the caterpillar can occur in inaccessible places or directly on the plant on which the larva fed. Under certain conditions, insects travel considerable distances in search of protected places. Later, a butterfly emerges from the pupa.

Habitat

The limited mobility of caterpillars does not facilitate their movement over long distances. In most cases, insects lead a terrestrial lifestyle, but there are also species that live in water.

All caterpillars are divided into two main groups: hidden and leading a free lifestyle. The former practically do not appear on the surface and live in the bark or in the ground away from sunlight. The latter are found on plants and are active during the daytime.

Habitat

In nature, many insects and animals feed on caterpillars. This is due to their high protein content. Therefore, the color of insects living on plants has a camouflage color, which allows them to blend in with the surface of the leaves. Poisonous butterfly larvae are characterized by a frightening bright body shade.

Among those who eat caterpillars:

- wasps;

- spiders;

- birds;

- reptiles.

To protect themselves from attacks from predators, some butterfly larvae are capable of producing a whistle and protruding from their body a fork-shaped gland of a red-orange hue, which secretes mucus with a pungent odor.

Pupal phase

This is an intermediate stage between the larva and the adult butterfly. When the caterpillars turn into pupae, they stop feeding and look for substrate for their final molt. As the pupal stage approaches, a metamorphosis hormone is produced, which ensures a change in developmental phases. Wings undergo rapid mitosis, so this stage requires a lot of nutrients. To protect themselves from predators, pupae make certain types of sounds.

Types of caterpillars in which the number and arrangement of legs differs from the usual

The order of butterflies includes a huge number of species and their caterpillars differ significantly in appearance from each other. The number and arrangement of larval limbs differs especially among the following representatives of Lepidoptera.

Moths or surveyors

This species has only two pairs of false legs. They are located on the 6th and 10th segments of the larval body. This family got its name due to its special method of movement. Caterpillars “walk” in the same way that people measure length with a span using their hand.

Scoops or bats

False limbs, located on 3-4 body segments, can be very poorly developed.

Primary toothed moths

The caterpillars of these butterflies have 3 additional pairs of abdominal legs. In total, the larva has 11 pairs of limbs.

Megalopygids or flannel moths

The larvae of this species have 7 pairs of false legs, which are located on segments 2-7 and 10.

Miners

Small caterpillars of this family of butterflies usually live inside plants and have completely reduced both thoracic and abdominal legs.

Recommendations

- Eleanor Ann Ormerod (1892). A Study Guide to Agricultural Entomology: A Guide to Insect Life Practices and Prevention Controls for Agricultural Professionals and Agricultural Students

. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Co. - Roger Fabian Anderson (January 1960). Forest and Shade Tree Entomology

. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-02739-3. - "Caterpillar". Dictionary.com. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. (accessed March 26, 2008).

- "Geometridae". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Internet. September 19, 2022.

- Hall, Donald W. (September 2014). "Featured Creatures: Hickory Horned Devil, Citheronia regalis

."

University of Florida, Department of Entomology and Nematology

. Retrieved September 19, 2022. - ^ a b

Scoble, MJ.

1995 Lepidoptera: form, function and diversity

. Oxford Univ. Click. ISBN 0-19-854952-0 - Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (1974). "Structure and functions of the larval eye of the Perga sawfly." Journal of Insect Physiology

.

20

(8):1565–1591. Doi:10.1016/0022-1910(74)90087-0. PMID 4854430. - ^ a b

Fischer, Thilo S.;

Michalski, Arthur; Hausmann, Axel (2019). "Geometrid caterpillar in Eocene Baltic amber (Lepidoptera, Geometridae)". Scientific reports

.

9

(1): Article number 17201. Bibcode: 2019 NatSR ... 917201F. Doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53734-w. PMC 6868187. PMID 31748672. - ^ a b

Mueller, Natalie (November 20, 2022). "German scientists have found a 44-million-year-old caterpillar." . Retrieved November 23, 2022. - ^ a b

Georgiou, Aristos (21 November 2022).

"Scientists discover 'exceptional' 44-million-year-old caterpillar preserved in amber." Newsweek

. Retrieved November 24, 2022. - Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (June 2005). Evolution of insects

. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5218-2149-0. - Martille, David (13 January 2022). “Scientists have accidentally discovered the oldest butterfly or moth fossils ever to exist.” Talk

. Retrieved November 24, 2022. - Kukal, O.; B. Heinrich and J. G. Duman (1988). "Behavioral thermoregulation in frost-resistant arctic caterpillars, Gynaeophora groenlandica

."

J. Exp.

Biol .

138

(1):181–193. - Bennett, V.A.; Lee, R.E.; Nauman, L. S.; Kukal, O. (2003). "Selection of overwintering microhabitats by the Arctic woolly bear caterpillar, Gynaephora groenlandica

" (PDF).

Cryo letters

.

24

(3): 191–200. PMID 12908029. - Green, E (1989). "Diet-induced developmental polymorphism in the caterpillar" (PDF). The science

.

243

(4891):643–646. Bibcode:1989Sci...243..643G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.1931. Doi:10.1126/science.243.4891.643. PMID 17834231. S2CID 23249256. - Dussour, D. E. (1988). "Biparental protective gift of eggs with an acquired plant alkaloid in the moth Utetheisa ornatrix

."

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

.

85

(16):5992–996. Bibcode:1988PNAS ... 85.5992D. doi:10.1073/psas.85.16.5992. PMC 281891. PMID 3413071. - Malaque, Ceila M. S.; Lucia Andrade; Geraldine Madalosso; Sandra Tomy; Flavio L. Tavares; Antonio S. Seguro (2006). "A case of hemolysis resulting from contact with a Lonomia

caterpillar in southern Brazil."

American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

.

74

(5):807–809. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.807. PMID 16687684. - Darby, Jean (1958). What is a butterfly

? Chicago: Benefic Press. clause 13. - Bura, V. L.; Rohwer, V. G.; Martin, P. R.; Yak, J. E. (2010). "Whistling in caterpillars (Amorpha juglandis, Bombycoidea): sound-producing mechanism and function." Journal of Experimental Biology

.

214

(Thu 1): 30–37. Doi:10.1242/jeb.046805. PMID 21147966. - Lycaenid butterflies and ants. Australian Museum (2009-10-14). Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- Record, Grant L.G.; Lee A. Dyer. (2002). "On the conditional nature of the defense of Neotropical caterpillars from their natural enemies." Ecology

.

83

(11):3108–3119. Doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3108:OTCNON]2.0.CO; 2. JSTOR 3071846. S2CID 14389136. - Terrence Fitzgerald. "Walking pine caterpillar." Web.cortland.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- Monarch butterfly. scienceprojectlab.com. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- Chamberlin, M.E.; M.E. King (1998). "Changes in transport and metabolism of reactive ions in the midgut during the fifth instar of the tobacco hornworm ( Manduca sexta

)".

J. Exp.

Zool .

280

(2):135–141. Doi:10.1002 / (SICI) 1097-010X (19980201) 280: 2 3.0.CO; 2-P. - Pearce, N. (1995). "Predatory and parasitic Lepidoptera: plant-dwelling carnivores" (PDF). Journal of the Society of Lepidopterists

.

49

(4): 412–453. - Rubinoff, Daniel; Haynes, William P. (2005). "The web caterpillar chases the snails." The science

.

309

(5734): 575. doi:10.1126/science.1110397. PMID 16040699. S2CID 42604851. - "Caterpillars of forests and woodlands of the Pacific Northwest." USGS.

- Lance, D. R.; Elkinton, J. S.; Schwalbe, K. P. (1987). "Behavior of late-instar gypsy moth larvae in high- and low-density populations." Ecological entomology

.

12

(3): 267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1987.tb01005.x. S2CID 86040007. - Tent caterpillars and gypsy moths. Dec.ny.gov. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- van Emden; H. F. (1999). “Insect resistance in transgenic host plants—some caveats.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America

.

92

(6):788–797. Doi:10.1093/aesa/92.6.788. - Diaz, H. J. (2005). "Developments in global epidemiology, syndromic classification, management and prevention of caterpillar infestations." I am.

J. Trop. Med. Hyg .

72

(3):347–357. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.347. PMID 15772333. - Redd, J.T.; Voorhees, R.E.; Torok, T.J. (2007). "Lepidopterism Outbreak at Boy Scout Camp." Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology

.

56

(6):952–955. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.002. PMID 17368636. - Kovacs, Pennsylvania; Cardoso, J; Entres, M; Novak E.M.; Werneck, L. C. (December 2006). "Fatal intracerebral hemorrhage caused by envenomation by the Lonomia obliqua caterpillar: a case report." Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria

.

64

(4):1030–2. Doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2006000600029. PMID 17221019. - Patel R.J., Shanbhag R.M. (1973). "Ophthalmia nodosa - (case history)." Indian J Ophthalmol

.

21

(4): 208. - Balit, C.R.; Ptolemy, H. S.; Geary, M. J.; Russell, R. C.; Isbister, G. K. (2001). "An outbreak of caterpillar dermatitis caused by airborne hairs of the common mistletoe moth (Euproctis edwardsi)." Medical Journal of Australia

.

175

(11–12): 641–3. Doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143760.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 11837874. S2CID 26910462. - Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (ed.). "For children: The Gates of Heaven, copy D, object 1 (Bentley 1, Erdman i, Keynes i)" For children: The Gates of Heaven." William Blake Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- 1 Kings 8:37

- Michael Ferber (2017). Dictionary of Literary Symbols

. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316780978. - Donna Spaulding Andreol; Veronica Molinari, ed. (2011). Women and Science from the 17th Century to the Present: Pioneers, Activists, and Protagonists

. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. paragraph 36. ISBN 9781443830676. - Donna Spaulding Andreol; Véronique Molinari, ed. (2011). Women and Science from the 17th Century to the Present: Pioneers, Activists, and Protagonists

. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. paragraph 40. ISBN 9781443830676. - Borya Sax (1998). The Serpent and the Swan: The Animal Bride in Folklore and Literature

. Univ. Tennessee Press. pp. ISBN 9780939923687. - Karl A. E. Enenkel; Mark S. Smith (2007). Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature, and the Visual Arts

. BRILL. paragraph 157. ISBN 9789047422365. - Karl A. E. Enenkel; Mark S. Smith (2007). Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature, and the Visual Arts

. BRILL. paragraph 161. ISBN 9789047422365. - Karl A. E. Enenkel; Mark S. Smith (2007). Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature, and the Visual Arts

. BRILL. paragraph 162. ISBN 9789047422365. - Borya Sax (1998). The Serpent and the Swan: The Animal Bride in Folklore and Literature

. Univ. Tennessee Press. pp. ISBN 9780939923687. - Sherry Ackerman (2009). Through the Looking Glass

. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. paragraph 103. ISBN 9781443804561. - Sherry Ackerman (2009). Through the Looking Glass

. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. paragraph 99. ISBN 9781443804561. - What's Alan Watching?: Mad Men

, "The Fog"

Classification

There are different types of caterpillars. This is primarily due to the diversity of the Lepidoptera themselves. Interestingly, the color of the larva does not always match the color of the adult. One classification of caterpillar species is based on what they eat.

- The group of polyphages is represented by their representatives who are completely indiscriminate in food and can eat any plants. These include moths, for example, wine hawkmoth, ocellated hawkmoth, blind hawkmoth, kaya bear, moths, peacock eye and others.

- The group of monophages includes caterpillars that feed only on one specific type of plant. These are cabbageweed, apple moth, silkworm and some others.

- The group of oligophages includes those who feed on a specific type of plant; they represent one family or type. These include: swallowtails, pine cutworm, polyxena and others.

- Xylophages are caterpillars whose food is wood or bark. This group is represented by leaf rollers, wood borers and others.

What do they eat?

Caterpillars are known for their insatiable appetite. They typically feed on the leaves of a variety of plants, although some may eat insects or other small animals. Leaf-eating species can cause significant damage to fruit trees, agricultural crops, ornamental plants, deciduous trees and shrubs. For example, cabbage moth caterpillars (Trichoplusia ni) can eat three times their body weight daily. In addition to the damage these caterpillars cause by eating the leaves of cabbage and related crops, the feces they produce, known as frass, can stain the leaves and make the plants unsellable. Examples of insect-eating caterpillars include Feniseca tarquinius, which preys on woolly aphids, and the Alesa amesis butterfly, which feeds on nymphs of insects of the order Homoptera.